Your labradoodle may look fluffy and innocent. But that fur baby may be transforming life as we know it—affecting America’s birth rate, job location choices, disaster evacuations, and more.

You know you do it. You let your cat steal the covers. Or feed your schnauzer schnitzel. Or let your beagle be the boss. In homes nationwide, pugs pull rank and pointers show you where to put their treats.

And if you have a canary, it’s in a coal mine. Because the American family as we knew it is no more.

Welcome to the “multispecies family”—and all it entails.

Transforming the American family

Treating pets like family has transformed the American family structure, says Andrea Laurent-Simpson, a sociologist at Dallas’ Southern Methodist University (SMU). In her new book, “Just Like Family: How Companion Animals Joined the Household” (New York University Press), she says the implications are huge.

“American pet-owners are transforming the cultural definition of family,” Laurent-Simpson said in a statement. “Dogs and cats are treated like children, siblings, grandchildren. In fact, the American Veterinary Medical Association found that 85 percent of dog-owners and 76 percent of cat-owners think of their pets as family.”

Breaking new ground in research

Breaking new ground in research

Laurent-Simpson’s work on the subject has won awards and appeared in scholarly journals like Symbolic Interaction, Sociological Forum, and Sociological Inquiry.

The science of sociology has devoted little research to the issue, however, so her book could make the fur fly as pet lovers and detractors weigh in.

“This book helps explain the presence of the multispecies family as a newly diversified, nontraditional family structure worthy of research,” Laurent-Simpson says. “Dogs and cats within the American family have a profound impact on things like fertility considerations, the parent-child relationship, family finances, involvement of extended family members, and the household structure itself.”

$103 billion spent on pets

Some sociologists argue that human-animal social interaction doesn’t exist because animals are incapable of human language. But Laurent-Simpson says the proof is out there. Mostly in how pet owners behave.

First, we put our money where our pets are. Americans spent $103 billion on their pets in 2020, a $6 billion increase over 2019.

Decisions, decisions

Next, before we make big decisions, we think: How will this affect Fifi and YoYo?

American families consider their pets in decisions on everything from child-rearing to home buying, Laurent-Simpson says. We factor them in when we think about job location, travel, budgets, and more.

Congress passes the PETS Act

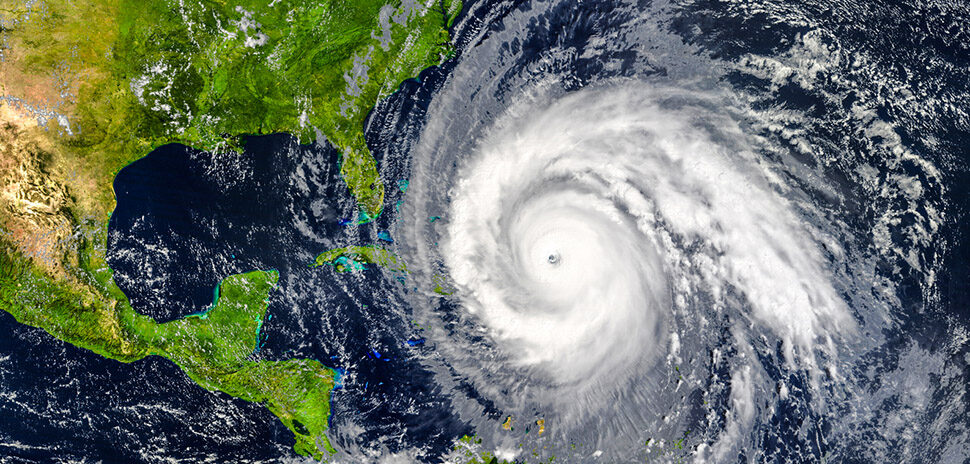

One life-or-death pet decision: whether to ride out a natural disaster. Laurent-Simpson notes that as Hurricane Katrina approached New Orleans in 2005, nearly half of the city’s residents refused to evacuate without their pets.

That led Congress to pass the PETS Act, which authorizes FEMA to rescue, shelter, and care for household pets during emergencies.

Pets have led to other laws, too. With pet custody battles raging in divorce courts nationwide, three states have passed divorce laws requiring courts to treat pets not as property but as—you guessed it—family members.

That may be wise, because many couples are choosing pets and ditching the idea of babies altogether.

Have pets lowered our birth rate?

The author’s biggest—and most controversial—suggestion is that the growing emphasis on the multispecies family has affected America’s declining birth rate. The U.S. total fertility rate, which measures the number of children born per 1,000 women, hit a record low in 2020. That continued a constant decline that began in 2007.

“The role of the companion animal in the child-free, multispecies family may well incrementally contribute to delaying or even eventually opting out of childbirth,” Laurent-Simpson asserts. “The multispecies family without children is emerging as a new and acceptable form of diversified family structure.”

In other words, who needs a baby when a bulldog will do?

Shifts began in the 1970s

Obviously, Daniel Boone loved his coon dog. People have always loved pets. But Laurent-Simpson says something big changed in the ’70s, a decade of massive demographic shifts.

“In order for the multispecies family to come to fruition in its current form, major society-level attitudinal shifts had to occur,” she says.

Nontraditional families are more common

The author ties the trend to a rise in nontraditional families. Single-parent families, child-free families, grandparent families, and LGBTQ families have all paved the way for the rise of the multispecies family, she says.

The sociologist doesn’t stop at the ’70s. She says some of the conditions that created the multispecies family go all the way back to the Industrial Revolution. That’s when families began to focus less on subsistence and more on loving, belonging, self-actualization, and self-happiness, Laurent-Simpson argues.

From infectious diseases to pets replacing kids

Multispecies families aren’t Laurent-Simpson’s only focus. She’s also conducted research on emerging infectious diseases, especially those like Zika virus that impact infertility. She examines how a wide array of things impact the spread of these diseases, including socioeconomic status; social media messages; and the clash of individual risk perceptions, preventive behavior, and risky behavior. Her work on on this project has also won awards, and has appeared or is soon be published in Sociology of Health and Illness and Sociological Spectrum.

The impact of “pandemic pets”

Now the SMU sociologist is tying her studies together, bridging her interest in disease with her work on human-animal connections. Her newest project will explore how “pandemic pets” have impacted different kinds of households and family members—not only during the lockdowns and quarantines, but when people began returning to work and school.

Did pandemic puppies help ease the social isolation of COVID? Or did they merely solidify the decades-long trend toward multispecies families? Only time and research will tell.

But one thing’s for sure: Laurent-Simpson lives what she studies. She dedicated her book to her own multispecies family—her husband, sons, and dogs.

![]()

Get on the list.

Dallas Innovates, every day.

Sign up to keep your eye on what’s new and next in Dallas-Fort Worth, every day.